Surveillance, Power, and Participation: Reimagining the Digital Social Contract in Africa

Vanessa GathechaAcross African cities, the face of state power is undergoing a shift. Teargas and riot police have not vanished, but they now operate alongside surveillance software, AI systems, and expansive data infrastructures.

.jpg)

Across African cities, the face of state power is undergoing a shift. Teargas and riot police have not vanished, but they now operate alongside surveillance software, AI systems, and expansive data infrastructures. Today, control is as likely to be exercised through an algorithm or a data-sharing clause as it is through a baton.

At a recent panel held by Edgelands Nairobi, two leading experts, Richard Ngamita, Co-founder of Thraets and Digital Policy Researcher Grace Mutung’u, unpacked this evolution. From physical crackdowns to digital coercion, from legal opacity to grassroots innovation, we explored how power, resistance, and participation are being redefined in Africa’s digital age.

From Riot Control to Predictive Policing

Kenya’s 2024 anti-Finance Bill protests marked a watershed moment as peaceful protests quickly escalated into a nationwide crisis, where online dissenters faced threats, abductions, and in several cases, extrajudicial killings. Many feared that exercising constitutionally protected rights, like protest and speech, had become life-threatening.

Richard Ngamita shared findings from "Israeli Gas, Kenyan Tears: An Investigation into the Israel-Supplied Riot Control Agents Used in the Kenya Demonstrations" a Thraets investigation connecting imported crowd-control weapons to obscure international financial flows, linking Israeli suppliers to local bank accounts in Kenya, painting a grim picture of transnational surveillance supply chains, reinforcing domestic repression.

Kenya, however, is not alone. From #EndSARS in Nigeria to mass mobilizations in Uganda, Ghana, Senegal, and South Africa, young, politically active Africans, many jobless or under-resourced, are turning to digital platforms to organize. Governments, in response, are investing in algorithmic policing tools, surveillance contracts, and telecommunications partnerships that allow covert monitoring at scale.

In many cases, telecoms have quietly become enablers of surveillance states, handing over user data or supporting location tracking with minimal public oversight.

When DigitalID Becomes a Tool of Control

We then turned to DigitalID systems, a central node in this expanding web of surveillance. While digital IDs are often framed as essential for inclusion and access to services, in countries with weak data protection, they risk becoming tools of exclusion and control.

Grace Mutung’u recounted Kenya’s stalled Huduma Namba rollout, where concerns around mandatory registration, opaque inter-agency data sharing, and lack of public consent triggered widespread pushback. A newer version, Maisha Namba, has been proposed, promising local development and cost savings, yet foundational questions remain unanswered: Who governs the data? Who can access it? And under what conditions?

Uganda offers a cautionary glimpse into the future with the third phase of its Smart Cities program, whereby surveillance cameras, biometric data, license plate recognition, and mobile money logs are now being integrated, creating an AI-powered, ambient surveillance infrastructure that’s always on.

Ghana’s more cautious approach, which involved voluntary DigitalID enrollment and some parliamentary oversight, stands in contrast. But even with better safeguards, regional consensus on privacy standards, legal protections, and independent oversight remains elusive.

The International Supply Chain of Surveillance

The surveillance infrastructure emerging in Africa is not just homegrown; it’s imported, financed, and fuelled by international players. Chinese tech giants like Huawei and ZTE have built “safe city” platforms across the continent. Israeli firms like NSO Group and Cellebrite have sold spyware tools now implicated in targeting activists. American and European firms, Palantir, Honeywell, and others, are embedded in biometric systems and data analytics programs from border controls to voter registration.

These foreign-built systems, which often bypass public debate and accountability and sold under the guise of safety and efficiency, can be repurposed for political control with chilling speed.

Policy vs. Practice: Closing the Gap

Africa doesn’t lack progressive digital rights frameworks; it lacks enforcement and local ownership. As Grace Mutung’u noted, policies often look good on paper but fail in practice because the public isn’t meaningfully involved. She pointed to Kenya’s AI and Robotics Bill as a chance to chart a new course. Like M-Pesa before it, Africa must shape emerging technologies in ways that fit local contexts. This means growing national AI talent, investing in local language processing, and creating models that reflect our own needs, not just relying on one-size-fits-all solutions from Silicon Valley.

Laws around data privacy, as well as new and emerging technologies, must be adaptable, and subsequently, AI regulation, data protection, and DigitalID frameworks must reflect the social, political, and economic realities of the places where they are applied.

Rewriting the Digital Social Contract

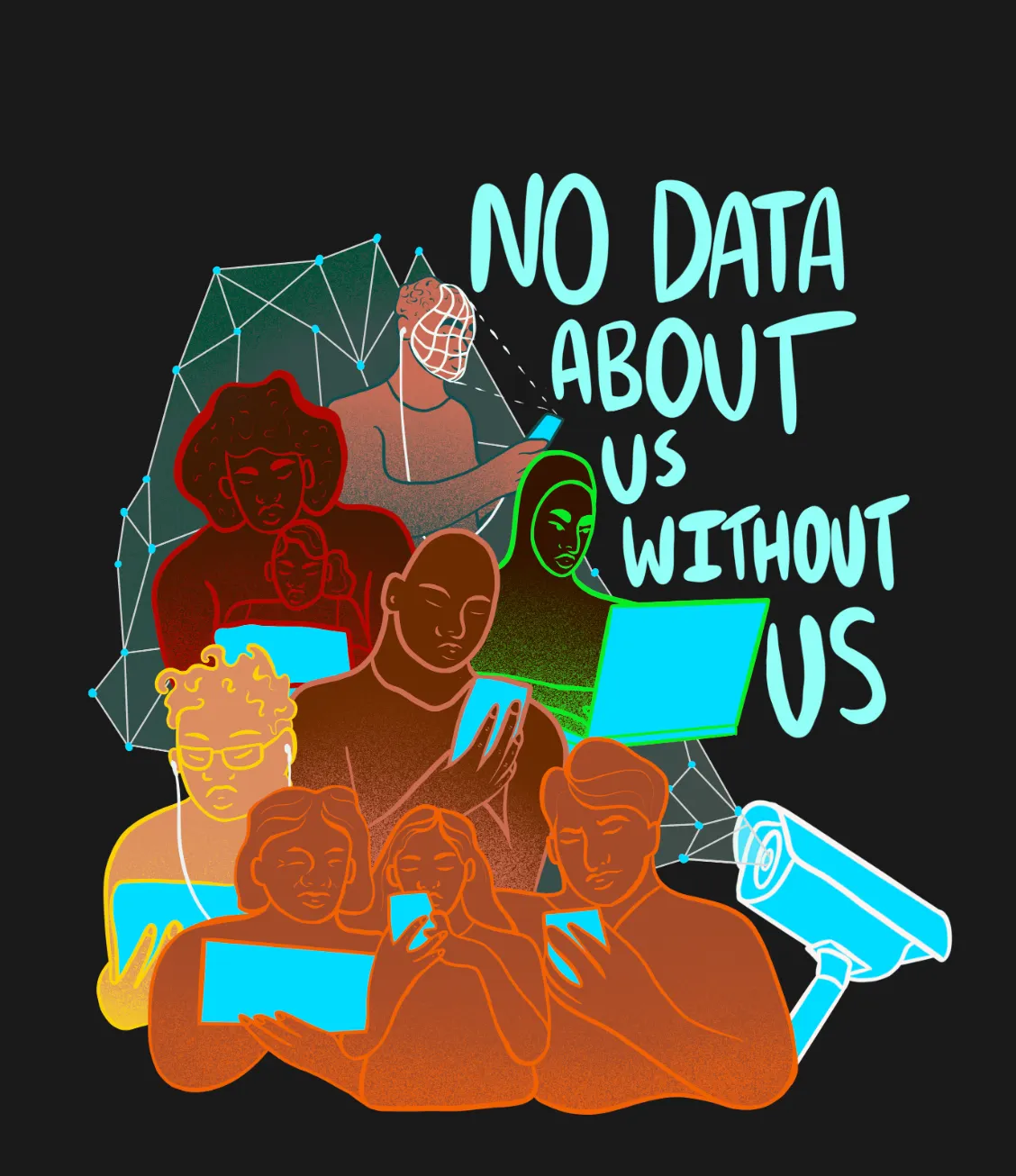

Africa is at a digital crossroads; the same tools that promise inclusion and efficiency can entrench authoritarianism if left unchecked. Reimagining the urban social contract in this digital era means building systems rooted in accountability, not coercion; inclusion, not extraction.

This begins with refusing to trade individual liberties for connectivity, instead, defining African technological futures on African terms, where civic agency drives the agenda, and local voices are heard at every step of the policymaking process. Surveillance should not be the price of public service, and public participation must never require permission.

As our panel made clear, the path forward demands vigilance, transparency, and collective imagination. The future is not just about who builds the tools, but equally, who decides how they're used.

Lessons from the Edgelands Nairobi Project

This panel discussion marked the conclusion of the Edgelands Nairobi project, part of the broader Edgelands Global initiative exploring digital security in urban settings. After months of leading country-specific work, this moment represents a deliberate step-back, a process we call “popping down”, to reflect and make space for what comes next. As we wrap up our time in Nairobi, we carry forward the insights and relationships built through participatory research on digital surveillance in the city’s urban peripheries.

From this work, the Edgelands Project surfaced five key takeaways that will shape our future collaborations and thinking:

- Participatory, Decentralised Research as a Mechanism for Risk Detection

Effective oversight of surveillance infrastructure requires the integration of community-driven, participatory research methods. These deliberative approaches are essential for identifying latent harms, mapping the lived experience of surveillance, and documenting emergent socio-technical risks that are often missed by centralised or technocratic assessments. Such methodologies democratise the knowledge-production process and strengthen civic engagement in digital governance.

- Legal and Regulatory Frameworks Must Be Context-Aware and Locally Embedded

Legislation governing DigitalID, surveillance, and data systems must reflect the socio-cultural, economic, and political contexts in which they operate. Overreliance on externally borrowed legal frameworks, often modelled after Euro-American paradigms, risks disconnecting law from lived reality. Instead, regulatory design must draw from indigenous legal traditions, community governance structures, and localised norms to ensure legitimacy, relevance, and enforceability.

- Surveillance Deployment Varies by Location and Socioeconomic Status

Surveillance infrastructure is not applied uniformly. Informal settlements and lower-income neighbourhoods are disproportionately subject to intrusive, state-led monitoring with minimal service reciprocity. In contrast, affluent urban areas increasingly adopt private, high-resolution security systems that serve proprietary interests. This spatial and economic asymmetry in surveillance design and access deepens structural inequality and reconfigures public safety along class lines.

- Surveillance Systems Must Be Contextually Analysed to Understand Their Impact

Technologies of surveillance do not operate in a vacuum, their impact is shaped by local technopolitical conditions, historical legacies of control, and institutional trust. The same tool may serve as a safety mechanism in one context and a repressive apparatus in another. Policymaking and system design must therefore be grounded in granular, context-sensitive analysis that accounts for power dynamics, civic capacity, and governance quality.

- Transparency, Accountability, and Public Oversight Are Non-Negotiable

The ethical deployment of surveillance technologies hinges on procedural transparency and institutional accountability. This includes clear disclosure of procurement practices, vendor affiliations, technical capabilities, data-sharing agreements, and oversight mechanisms. Public participation must be embedded across the lifecycle of surveillance systems, from design to deployment to evaluation, ensuring there are systems of redress, and that state and corporate actors are answerable to affected communities and the broader public.

We hope the Edgelands Nairobi Project lives on, driven by the conversations it has started, the collaborations it has enabled, and the awareness it has raised. You can explore the full findings in our Nairobi Project Pop-Down Report.

We extend our deep thanks to panellists Grace Mutung’u and Richard Ngamita for their valuable insights, and to Cynthia Chepkemoi, Research Associate at Edgelands Nairobi, whose contributions and ongoing support were vital to the success of this work.

We’re also deeply grateful to our partners across Africa, whose long-standing collaboration and commitment made this research project possible.